Sometimes a book comes to you at exactly the right moment in your life. At first, you think it must be a fluke; certainly there will be a fork in the story where the plot deviates from your own reality. But then, sentence after sentence continues to feel like it was constructed personally with your own world in mind. This is a rare experience, and one that should be treasured.

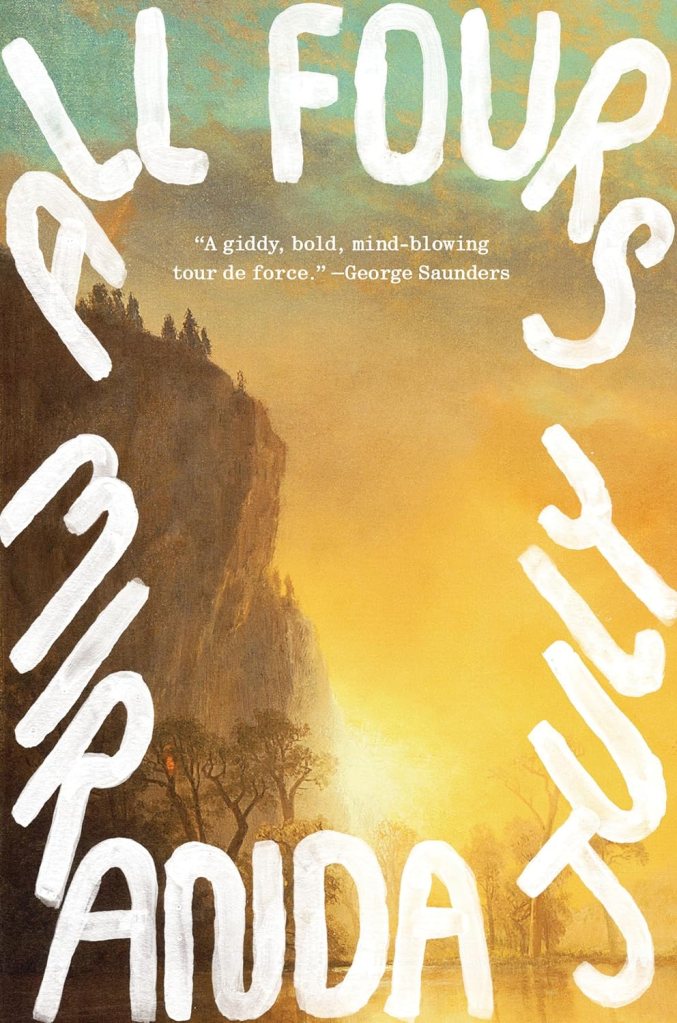

This was my experience reading Miranda July’s 2024 novel All Fours.

The first-person narrator is a 45 year-old, semi-famous artist. She and her husband have been together for 15 years, and share a six year-old child, who came into the world via a traumatic birth. The narrator, who lives in Los Angeles, has plans to visit New York. Having never taken a road trip, she decides to drive. She makes it all of 30 minutes outside of Los Angeles before holing up at a motel in Monrovia for two weeks, and setting the wheels in motion on a journey that will upend her relationships, her health, and her way of seeing the world.

I should now include a caveat that I have not seen/read/experienced any of July’s other work. There may be some other layers to opinions about this book (my own included) that are rooted in an understanding of her broader body of work, but I did not have that coloring my experience of this book — for better or for worse. (As overwhelming as this book was, I am almost inclined not to see her films or read her other stories at risk of damaging the surface tension of this story. But we’ll circle back to that.)

Back to the book. July does not hold back in her depictions of motherhood, of sex and sexual desire, of marriage. Many of her observations feel like thoughts we all think everyone else is having, but we are all too scared to say out loud. Reading them on the page, hearing them in July’s soft voice, felt like it was changing my life in real time. Raw snippets of conversation would be followed by a metaphor so breathtaking I was jealous I had never thought to describe a sky or a road that way — and then sad that I had never seen it that way — and then hopeful that I could.

All Fours feels like a spiritual successor to Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be and Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick. Stories of creative women approaching middle age, considering the significance of their relationships, their sexuality, their bodies, their minds. Small and insignificant interactions suddenly exploding with meaning. Kraus once referred to her work as occupying the sphere of “lonely girl phenomenology.” Many, many people hate these women and their stories.

From professional critics to the trenches of GoodReads, you will find declarative statements using words like “icky,” “annoying,” “narcissistic” being made in reference to these books. Many, thinking themselves clever, have proclaimed “these books have no point!” The only solution, therefore, must be the woman’s own insufferable self-obsession, leading her to create such a mindless and inconsequential product. Sometimes I mistakenly think feminism has made progress, and then I peek online to find the most ardent critiques of a book like All Fours have more to do with the narrator’s failings as a wife and mother.

There is power in these reactions, I suppose. They are in many ways tied to what makes All Fours so brilliant. It captures a feeling, a reality that so many people live with tightly coiled inside themselves. The reactions to the book prove why it must remain inside. Freedom + unfiltered self-expression + grotesque curiosity + uncertainty = bad and undesirable woman. Experiencing these feelings through the page is as close as many people get to living the lives they know they are capable of.

Though I felt seen line after line, I am decidedly not a 45 year-old, peri-menopausal mother. I am 31 years old and only beginning to grasp the outline of the next stage of my life. Reading the book felt like opening a tome of wisdom of women who came before me. “Here’s what to know” it says. “Now go ahead and don’t be afraid to live the life you want.”